Home | Image Library | Blog | Purchasing | Contact | About | Search

May 15, 2018 - Sonoma Coast Wildflowers

I've been fascinated by non-photosynthesizing plants ever since I first read about the phantom orchid in Michael Graf's Plants of the Tahoe Basin. Sure, these unique organisms may not have the same flamboyance as their carnivorous cousins, but there's still something quite intriguing about plants that don't require any sunlight in order to grow. As such, they tend to thrive in shady habitats where there is reduced competition from plants that obtain their energy in the "traditional" manner. As a photographer, I can especially appreciate this — not only is it nice to not have the sun beating down on the back of my neck, but the forest canopy does most of the heavy lifting in terms of softening those harsh rays.

Over the years, I've had the joy of finding and photographing a number of non-photosynthesizing plants. Snow plant, whose bright red color practically screams for attention, is easy to spot even at highway speeds (not that I endorse botanizing while driving). Spotted coralroot and woodland pinedrops may not be quite as conspicuous, but are common enough to still be regularly encountered by anyone who spends enough time in the forest. Striped coralroot and the aforementioned phantom orchid tend to be harder to find, but can still be located with a bit of research and exploration. However, sugarstick and Pacific coralroot are two non-photosynthesizing species that have eluded me for quite some time. They don't seem to have a reputation of being especially rare or endangered — I had apparently just never been at the right place at the right time...that is, until May 5th, when I headed out to the Sonoma coast in hopes of finding them both.

Over the years, I've had the joy of finding and photographing a number of non-photosynthesizing plants. Snow plant, whose bright red color practically screams for attention, is easy to spot even at highway speeds (not that I endorse botanizing while driving). Spotted coralroot and woodland pinedrops may not be quite as conspicuous, but are common enough to still be regularly encountered by anyone who spends enough time in the forest. Striped coralroot and the aforementioned phantom orchid tend to be harder to find, but can still be located with a bit of research and exploration. However, sugarstick and Pacific coralroot are two non-photosynthesizing species that have eluded me for quite some time. They don't seem to have a reputation of being especially rare or endangered — I had apparently just never been at the right place at the right time...that is, until May 5th, when I headed out to the Sonoma coast in hopes of finding them both.

My search began at Kruse Rhododendron State Natural Reserve. This is a place I originally visited several years ago in search of mushrooms, but have since come to appreciate for its wonderful array of wildflowers. From CA-1, head east on Kruse Ranch Road for just under half a mile and park on either side of the road. There's only room for about a dozen cars, but I've never had trouble finding a spot before, and parking is free. Chinese Gulch Trail begins on the left side of the road, and Phillips Gulch Trail begins on the right. I took the latter, although it makes little difference since the trails form a loop.

As I followed the switchbacks to make my descent, I passed by several Pacific trilliums (trillia?). Most had already gone to seed, but I was surprised to find a handful still in excellent condition. Redwood sorrel and redwood violets were all over the place, which is to be expected; it is a redwood forest after all. There were even some fairy slipper orchids scattered about. These little gems were a pleasure to see despite clearly being past their prime. I occasionally noticed some promising plants from a distance, but they kept turning out to be spotted coralroot upon closer inspection. All of these familiar plants made for a wonderfully scenic hike, but they were not the reason I drove over two and a half hours to the coast that Saturday. I kept chugging away, and it eventually paid off when I finally discovered my very first Pacific coralroot. It was about a mile into the hike, just left of the T junction and before the trail crosses the road to continue to the Chinese Gulch Trail. Note: I can't find this junction on any official map, but it is very obvious when you reach it. I'm not sure where the right direction leads.

As I followed the switchbacks to make my descent, I passed by several Pacific trilliums (trillia?). Most had already gone to seed, but I was surprised to find a handful still in excellent condition. Redwood sorrel and redwood violets were all over the place, which is to be expected; it is a redwood forest after all. There were even some fairy slipper orchids scattered about. These little gems were a pleasure to see despite clearly being past their prime. I occasionally noticed some promising plants from a distance, but they kept turning out to be spotted coralroot upon closer inspection. All of these familiar plants made for a wonderfully scenic hike, but they were not the reason I drove over two and a half hours to the coast that Saturday. I kept chugging away, and it eventually paid off when I finally discovered my very first Pacific coralroot. It was about a mile into the hike, just left of the T junction and before the trail crosses the road to continue to the Chinese Gulch Trail. Note: I can't find this junction on any official map, but it is very obvious when you reach it. I'm not sure where the right direction leads.

I actually noticed over a dozen Pacific coralroot clusters in that general vicinity. They suddenly seemed so commonplace that I began to wonder if I had been hiking past them all the while. In any case, I had plenty to choose from, so I spent a good hour finding the best specimens and photographing them. I found a few more on the Chinese Gulch Trail at some point after crossing the road, but the highest concentration definitely seemed to be between the T junction and Kruse Ranch Road.

After photographing a few other subjects along the way, I eventually completed the loop back to my car around 5:30 PM. No sign of sugarstick. Checking one item off my list was indeed satisfying, but I still wanted to find the other. Fortunately, I had a good idea where to look and just enough time to get there. I headed back down highway 1 for a few miles and turned left into Salt Point's Woodside Campground parking lot. For the casual tourist looking for unusual rock formations and pretty sunsets, Gerstle Cove across the highway is definitely the way to go. However, I was a man on a mission to find a cool plant, and I knew where I was most likely to find it based on historical observations. I grabbed my equipment, checked the time with a bit of apprehension, and began hiking up Central Trail.

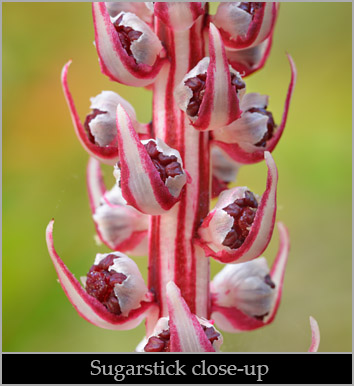

Salt Point was home to many of the same plants I had seen earlier in the day (it's basically the same forest, after all), but there were different finds as well, including some very late-blooming Indian warrior. However, with the sky growing darker by the minute, I really didn't have any time to spare. I kept pushing forward, eventually passing up the Water Tank Trail on my left. A few minutes past that point, I was honestly beginning to think my chances of finding sugarstick were pretty slim. Should I have taken that trail to the left? Had I arrived too early in the season? Maybe there just hadn't been enough rainfall this year (these non-photosynthetic plants rely on subterranean fungi for nourishment, and fungi need a lot of water). Thankfully, I didn't have to go too much further before all those worries were cast aside. On the right side of the trail, in completely plain sight, was an immaculate collection of sugarstick. Some of the stalks were still just getting started, but I didn't mind. This allowed me to show the plants at different stages all within a single shot. It also allowed me some time to write this article and still have it be relevant (that is, some of the plants should still be in good condition now, even though it has taken me ten days to finish writing about them — sorry for the delay!).

Salt Point was home to many of the same plants I had seen earlier in the day (it's basically the same forest, after all), but there were different finds as well, including some very late-blooming Indian warrior. However, with the sky growing darker by the minute, I really didn't have any time to spare. I kept pushing forward, eventually passing up the Water Tank Trail on my left. A few minutes past that point, I was honestly beginning to think my chances of finding sugarstick were pretty slim. Should I have taken that trail to the left? Had I arrived too early in the season? Maybe there just hadn't been enough rainfall this year (these non-photosynthetic plants rely on subterranean fungi for nourishment, and fungi need a lot of water). Thankfully, I didn't have to go too much further before all those worries were cast aside. On the right side of the trail, in completely plain sight, was an immaculate collection of sugarstick. Some of the stalks were still just getting started, but I didn't mind. This allowed me to show the plants at different stages all within a single shot. It also allowed me some time to write this article and still have it be relevant (that is, some of the plants should still be in good condition now, even though it has taken me ten days to finish writing about them — sorry for the delay!).

With daylight quickly dwindling away, I knew I should get right to work, but I nevertheless found myself simply marveling at the red and white botanical wonder. Not all plants are very aptly named, but sugarstick really does look like something you'd expect to find in a candy shop. I'll admit I was tempted to try a bite; anything that looks that good must be delicious, right? Fortunately, I had the good sense to start taking pictures before my appetite got the better of me. Sugarstick may not actually be candy, but it sure is a sweet find.

Previous Entry: February 24, 2018 - Fairy Slippers Now in Bloom

Blog Archive

![]()

Interested in buying a print or licensing a picture? Click on the purchasing link for more information or contact us with any questions you may have. Thanks for looking!

Back To Top

All images & text copyright Timothy Boomer. All rights reserved worldwide.